Digging the Adobe Sandbox - IPC Internals

This post kicks off a short series into reversing the Adobe Reader sandbox. I initially started this research early last year and have been working on it off and on since. This series will document the Reader sandbox internals, present a few tools for reversing/interacting with it, and a description of the results of this research. There may be quite a bit of content here, but I’ll be doing a lot of braindumping. I find posts that document process, failure, and attempt to be far more insightful as a researcher than pure technical result.

I’ve broken this research up into two posts. Maybe more, we’ll see. The first here will detail the internals of the sandbox and introduce a few tools developed, and the second will focus on fuzzing and the results of that effort.

This post focuses primarily on the IPC channel used to communicate between the sandboxed process and the broker. I do not delve into how the policy engine works or many of the restrictions enabled.

Introduction

This is by no means the first dive into the Adobe Reader sandbox. Here are a few prior examples of great work:

2011 - A Castle Made of Sand (Richard Johnson)

2011 - Playing in the Reader X Sandbox (Paul Sabanal and Mark Yason)

2012 - Breeding Sandworms (Zhenhua Liu and Guillaume Lovet)

2013 - When the Broker is Broken (Peter Vreugdenhil)

Breeding Sandworms was a particularly useful introduction to the sandbox, as it describes in some detail the internals of transaction and how they approached fuzzing the sandbox. I’ll detail my approach and improvements in

part two of this series.

In addition, the ZDI crew of Abdul-Aziz Hariri, et al. have been hammering on the Javascript side of things for what seems like forever (Abusing Adobe Reader’s Javascript APIs) and have done some great work in this area.

After evaluating existing research, however, it seemed like there was more work to be done in a more open source fashion. Most sandbox escapes in Reader these days opt instead to target Windows itself via win32k/dxdiag/etc and not the sandbox broker. This makes some sense, but leaves a lot of attack surface unexplored.

Note that all research was done on Acrobat Reader DC 20.6.20034 on a Windows 10 machine. You can fetch installers for old versions of Adobe Reader here. I highly recommend bookmarking this. One of my favorite things to do on a new target is pull previous bugs and affected versions and run through root cause and exploitation.

Sandbox Internals Overview

Adobe Reader’s sandbox is known as protected mode and is on by default, but can be toggled on/off via preferences or the registry. Once Reader launches, a child process is spawned under low integrity and a shared memory section mapped in. Inter-process communication (IPC) takes place over this channel, with the parent process acting as the broker.

Adobe actually published some of the sandbox source code to Github over 7 years ago, but it does not contain any of their policies or modern tag interfaces. It’s useful for figuring out variables and function names during reversing, and the source code is well written and full of useful comments, so I recommend pulling it up.

Reader uses the Chromium sandbox (pre Mojo), and I recommend the following resources for the specifics here:

These days it’s known as the “legacy IPC” and has been replaced by Mojo in Chrome. Reader actually uses Mojo to communicate between its RdrCEF (Chromium Embedded Framework) processes which handle cloud connectivity, syncing, etc. It’s possible Adobe plans to replace the broker legacy API with Mojo at some point, but this has not been announced/released yet.

We’ll start by taking a brief look at how a target process is spawned, but the main focus of this post will be the guts of the IPC mechanisms in play. Execution of the child process first begins with BrokerServicesBase::SpawnTarget. This function crafts the target process and its restrictions. Some of these are described here in greater detail, but they are as follows:

1. Create restricted token

- via `CreateRestrictedToken`

- Low integrity or AppContainer if available

2. Create restricted job object

- No RW to clipboard

- No access to user handles in other processes

- No message broadcasts

- No global hooks

- No global atoms table access

- No changes to display settings

- No desktop switching/creation

- No ExitWindows calls

- No SystemParamtersInfo

- One active process

- Kill on close/unhandled exception

From here, the policy manager enforces interceptions, handled by the InterceptionManager, which handles hooking and rewiring various Win32 functions via the target process to the broker. According to documentation, this is not for security, but rather:

[..] designed to provide compatibility when code inside the sandbox cannot be modified to cope with sandbox restrictions. To save unnecessary IPCs, policy is also evaluated in the target process before making an IPC call, although this is not used as a security guarantee but merely a speed optimization.

From here we can now take a look at how the IPC mechanisms between the target and broker process actually work.

The broker process is responsible for spawning the target process, creating a shared memory mapping, and initializing the requisite data structures. This shared memory mapping is the medium in which the broker and target communicate and exchange data. If the target wants to make an IPC call, the following happens at a high level:

- The target finds a channel in a free state

- The target serializes the IPC call parameters to the channel

- The target then signals an event object for the channel (ping event)

- The target waits until a pong event is signaled

At this point, the broker executes ThreadPingEventReady, the IPC processor entry point, where the following occurs:

- The broker deserializes the call arguments in the channel

- Sanity checks the parameters and the call

- Executes the callback

- Writes the return structure back to the channel

- Signals that the call is completed (pong event)

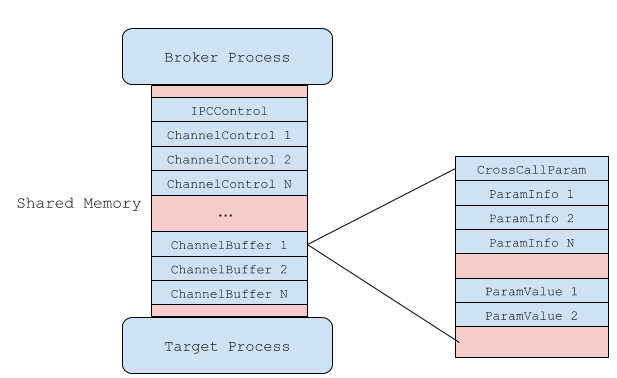

There are 16 channels available for use, meaning that the broker can service up to 16 concurrent IPC requests at a time. The following diagram describes a high level view of this architecture:

From the broker’s perspective, a channel can be viewed like so:

In general, this describes what the IPC communication channel between the broker and target looks like. In the following sections we’ll take a look at these in more technical depth.

IPC Internals

The IPC facilities are established via TargetProcess::Init, and is really what we’re most interested in. The following snippet describes how the shared memory mapping is created and established between the broker and target:

DWORD shared_mem_size = static_cast<DWORD>(shared_IPC_size +

shared_policy_size);

shared_section_.Set(::CreateFileMappingW(INVALID_HANDLE_VALUE, NULL,

PAGE_READWRITE | SEC_COMMIT,

0, shared_mem_size, NULL));

if (!shared_section_.IsValid()) {

return ::GetLastError();

}

DWORD access = FILE_MAP_READ | FILE_MAP_WRITE;

base::win::ScopedHandle target_shared_section;

if (!::DuplicateHandle(::GetCurrentProcess(), shared_section_,

sandbox_process_info_.process_handle(),

target_shared_section.Receive(), access, FALSE, 0)) {

return ::GetLastError();

}

void* shared_memory = ::MapViewOfFile(shared_section_,

FILE_MAP_WRITE|FILE_MAP_READ,

0, 0, 0);

The calculated shared_mem_size in the source code here comes out to 65536 bytes, which isn’t right. The shared section is actually 0x20000 bytes in modern Reader binaries.

Once the mapping is established and policies copied in, the SharedMemIPCServer

is initialized, and this is where things finally get interesting. SharedMemIPCServer initializes the ping/pong events for communication, creates channels, and registers callbacks.

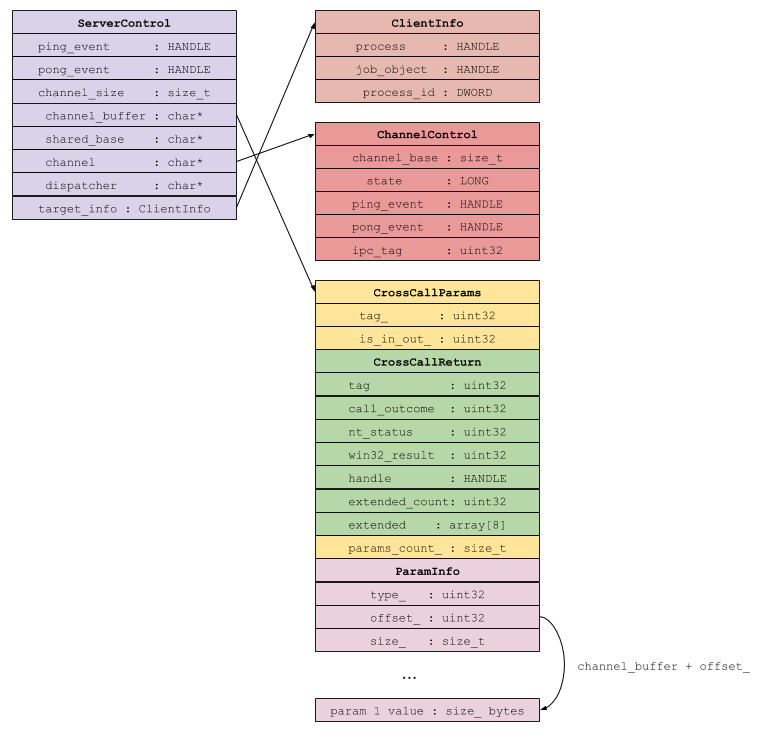

The previous architecture diagram provides an overview of the structures and layout of the section at

runtime. In short, a ServerControl is a broker-side view of an IPC channel. It contains the server side event handles, pointers to both the channel and its buffer, and general information about the connected IPC endpoint. This structure is not visible to the target process and exists only in the broker.

A ChannelControl is the target process version of a ServerControl; it contains the target’s event handles, the state of the channel, and information about where to find the channel buffer. This channel buffer is where the CrossCallParams can be found as well as the call return information after a successful IPC dispatch.

Let’s walk through what an actual request looks like. Making an IPC request requires the target to first prepare a CrossCallParams structure. This is defined as a class, but we can model it as a struct:

const size_t kExtendedReturnCount = 8;

struct CrossCallParams {

uint32 tag_;

uint32 is_in_out_;

CrossCallReturn call_return;

size_t params_count_;

};

struct CrossCallReturn {

uint32 tag_;

uint32 call_outcome;

union {

NTSTATUS nt_status;

DWORD win32_result;

};

HANDLE handle;

uint32 extended_count;

MultiType extended[kExtendedReturnCount];

};

union MultiType {

uint32 unsigned_int;

void* pointer;

HANDLE handle;

ULONG_PTR ulong_ptr;

};

I’ve also gone ahead and defined a few other structures needed to complete the picture. Note that the return structure, CrossCallReturn, is embedded within the body of the CrossCallParams.

There’s a great ASCII diagram provided in the sandbox source code that’s highly instructive, and I’ve duplicated it below:

// [ tag 4 bytes]

// [ IsOnOut 4 bytes]

// [ call return 52 bytes]

// [ params count 4 bytes]

// [ parameter 0 type 4 bytes]

// [ parameter 0 offset 4 bytes] ---delta to ---\

// [ parameter 0 size 4 bytes] |

// [ parameter 1 type 4 bytes] |

// [ parameter 1 offset 4 bytes] ---------------|--\

// [ parameter 1 size 4 bytes] | |

// [ parameter 2 type 4 bytes] | |

// [ parameter 2 offset 4 bytes] ----------------------\

// [ parameter 2 size 4 bytes] | | |

// |---------------------------| | | |

// | value 0 (x bytes) | <--------------/ | |

// | value 1 (y bytes) | <-----------------/ |

// | | |

// | end of buffer | <---------------------/

// |---------------------------|

A tag is a dword indicating which function we’re invoking (just a number between 1 and approximately 255, depending on your version). This is handled server side dynamically, and we’ll explore that further later on.

Each parameter is then sequentially represented by a ParamInfo structure:

struct ParamInfo {

ArgType type_;

ptrdiff_t offset_;

size_t size_;

};

The offset is the delta value to a region of memory somewhere below the CrossCallParams structure. This is handled in the Chromium source code via the ptrdiff_t type.

Let’s look at a call in memory from the target’s perspective. Assume the channel buffer is at 0x2a10134:

0:009> dd 2a10000+0x134

02a10134 00000003 00000000 00000000 00000000

02a10144 00000000 00000000 000002cc 00000001

02a10154 00000000 00000000 00000000 00000000

02a10164 00000000 00000000 00000000 00000007

02a10174 00000001 000000a0 00000086 00000002

02a10184 00000128 00000004 00000002 00000130

02a10194 00000004 00000002 00000138 00000004

02a101a4 00000002 00000140 00000004 00000002

0x2a10134 shows we’re invoking tag 3, which carries 7 parameters (0x2a10170).

The first argument is type 0x1 (we’ll describe types later on), is at delta

offset 0xa0, and is 0x86 bytes in size. Thus:

0:009> dd 2a10000+0x134+0xa0

02a101d4 003f005c 005c003f 003a0043 0055005c

02a101e4 00650073 00730072 0062005c 0061006a

02a101f4 006a0066 0041005c 00700070 00610044

02a10204 00610074 004c005c 0063006f 006c0061

02a10214 006f004c 005c0077 00640041 0062006f

02a10224 005c0065 00630041 006f0072 00610062

02a10234 005c0074 00430044 0052005c 00610065

02a10244 00650064 004d0072 00730065 00610073

0:009> du 2a10000+0x134+0xa0

02a101d4 "\??\C:\Users\bjaff\AppData\Local"

02a10214 "Low\Adobe\Acrobat\DC\ReaderMessa"

02a10254 "ges"

This shows the delta of the parameter data and, based on the parameter type, we know it’s a unicode string.

With this information, we can craft a buffer targeting IPC tag 3 and move onto sending it. To do this, we require the IPCControl structure. This is a simple structure defined at the start of the IPC shared memory section:

struct IPCControl {

size_t channels_count;

HANDLE server_alive;

ChannelControl channels[1];

};

And in the IPC shared memory section:

0:009> dd 2a10000

02a10000 0000000f 00000088 00000134 00000001

02a10010 00000010 00000014 00000003 00020134

So we have 16 channels, a handle to server_alive, and the start of our

ChannelControl array.

The server_alive handle is a mutex used to signal if the server has crashed.

It’s used during tag invocation in SharedmemIPCClient::DoCall, which we’ll describe later on. For now, assume that if we WaitForSingleObject on this and it returns WAIT_ABANDONED, the server has crashed.

ChannelControl is a structure that describes a channel, and is again defined as:

struct ChannelControl {

size_t channel_base;

volatile LONG state;

HANDLE ping_event;

HANDLE pong_event;

uint32 ipc_tag;

};

The channel_base describes the channel’s buffer, ie. where the CrossCallParams structure can be found. This is an offset from the base of the shared memory section.

state is an enum that describes the state of the channel:

enum ChannelState {

kFreeChannel = 1,

kBusyChannel,

kAckChannel,

kReadyChannel,

kAbandonnedChannel

};

The ping and pong events are, as previously described, used to signal to the opposite endpoint that data is ready for consumption. For example, when the client has written out its CrossCallParams and ready for the server, it signals:

DWORD wait = ::SignalObjectAndWait(channel[num].ping_event,

channel[num].pong_event,

kIPCWaitTimeOut1,

FALSE);

When the server has completed processing the request, the pong_event is signaled and the client reads back the call result.

A channel is fetched via SharedMemIPCClient::LockFreeChannel and is invoked when GetBuffer is called. This simply identifies a channel in the IPCControl array wherein state == kFreeChannel, and sets it to kBusyChannel. With a

channel, we can now write out our CrossCallParams structure to the shared memory buffer. Our target buffer begins at channel->channel_base.

Writing out the CrossCallParams has a few nuances. First, the number of

actual parameters is NUMBER_PARAMS+1. According to the source:

// Note that the actual number of params is NUMBER_PARAMS + 1

// so that the size of each actual param can be computed from the difference

// between one parameter and the next down. The offset of the last param

// points to the end of the buffer and the type and size are undefined.

This can be observed in the CopyParamIn function:

param_info_[index + 1].offset_ = Align(param_info_[index].offset_ +

size);

param_info_[index].size_ = size;

param_info_[index].type_ = type;

Note the offset written is the offset for index+1. In addition, this offset is aligned. This is a pretty simple function that byte aligns the delta inside the channel buffer:

// Increases |value| until there is no need for padding given the 2*pointer

// alignment on the platform. Returns the increased value.

// NOTE: This might not be good enough for some buffer. The OS might want the

// structure inside the buffer to be aligned also.

size_t Align(size_t value) {

size_t alignment = sizeof(ULONG_PTR) * 2;

return ((value + alignment - 1) / alignment) * alignment;

}

Because the Reader process is x86, the alignment is always 8.

The pseudo-code for writing out our CrossCallParams can be distilled into the following:

write_uint(buffer, tag);

write_uint(buffer+0x4, is_in_out);

// reserve 52 bytes for CrossCallReturn

write_crosscall_return(buffer+0x8);

write_uint(buffer+0x3c, param_count);

// calculate initial delta

delta = ((param_count + 1) * 12) + 12 + 52;

// write out the first argument's offset

write_uint(buffer + (0x4 * (3 * 0 + 0x11)), delta);

for idx in range(param_count):

write_uint(buffer + (0x4 * (3 * idx + 0x10)), type);

write_uint(buffer + (0x4 * (3 * idx + 0x12)), size);

// ...write out argument data. This varies based on the type

// calculate new delta

delta = Align(delta + size)

write_uint(buffer + (0x4 * (3 * (idx+1) + 0x11)), delta);

// finally, write the tag out to the ChannelControl struct

write_uint(channel_control->tag, tag);

Once the CrossCallParams structure has been written out, the sandboxed process signals the ping_event and the broker is triggered.

Broker side handling is fairly straightforward. The server registers a ping_event handler during SharedMemIPCServer::Init:

thread_provider_->RegisterWait(this, service_context->ping_event,

ThreadPingEventReady, service_context);

RegisterWait is just a thread pool wrapper around a call to RegisterWaitForSingleObject.

The ThreadPingEventReady function marks the channel as kAckChannel, fetches a pointer to the provided buffer, and invokes InvokeCallback. Once this

returns, it copies the CrossCallReturn structure back to the channel and signals the pong_event mutex.

InvokeCallback parses out the buffer and handles validation of data, at a high level (ensures strings are strings, buffers and sizes match up, etc.). This is probably a good time to document the supported argument types. There are 10 types in total, two of which are placeholder:

ArgType = {

0: "INVALID_TYPE",

1: "WCHAR_TYPE",

2: "ULONG_TYPE",

3: "UNISTR_TYPE", # treated same as WCHAR_TYPE

4: "VOIDPTR_TYPE",

5: "INPTR_TYPE",

6: "INOUTPTR_TYPE",

7: "ASCII_TYPE",

8: "MEM_TYPE",

9: "LAST_TYPE"

}

These are taken from internal_types,

but you’ll notice there are two additional types: ASCII_TYPE and MEM_TYPE, and are unique to Reader. ASCII_TYPE is, as expected, a simple 7bit ASCII string. MEM_TYPE is a memory structure used by the broker to read

data out of the sandboxed process, ie. for more complex types that can’t be trivially passed via the API. It’s additionally used for data blobs, such as PNG images, enhanced-format datafiles, and more.

Some of these types should be self-explanatory; WCHAR_TYPE is naturally a wide char, ASCII_TYPE an ascii string, and ULONG_TYPE a ulong. Let’s look at a few of the non-obvious types, however: VOIDPTR_TYPE, INPTR_TYPE, INOUTPTR_TYPE, and MEM_TYPE.

Starting with VOIDPTR_TYPE, this is a standard type in the Chromium sandbox so we can just refer to the source code. SharedMemIPCServer::GetArgs calls GetParameterVoidPtr. Simply, once the value itself is extracted it’s cast to a void ptr:

*param = *(reinterpret_cast<void**>(start));

This allows tags to reference objects and data within the broker process itself. An example might be NtOpenProcessToken, whose first parameter is a handle to the target process. This would be retrieved first by a call to OpenProcess, handed back to the child process, and then supplied in any future calls that may need to use the handle as a VOIDPTR_TYPE.

In the Chromium source code, INPTR_TYPE is extracted as a raw value via GetRawParameter and no additional processing is performed. However, in Adobe Reader, it’s actually extracted in the same way INOUTPTR_TYPE is.

INOUTPTR_TYPE is wrapped as a CountedBuffer and may be written to during the IPC call. For example, if CreateProcessW is invoked, the PROCESS_INFORMATION pointer will be of type INOUTPTR_TYPE.

The final type is MEM_TYPE, which is unique to Adobe Reader. We can define the structure as:

struct MEM_TYPE {

HANDLE hProcess;

DWORD lpBaseAddress;

SIZE_T nSize;

};

As mentioned, this type is primarily used to transfer data buffers to and from the broker process. It seems crazy. Each tag is responsible for performing its own validation of the provided values before they’re used in any ReadProcessMemory/WriteProcessMemory call.

Once the broker has parsed out the passed arguments, it fetches the context dispatcher and identifies our tag handler:

ContextDispatcher = *(int (__thiscall ****)(_DWORD, int *, int *))(Context + 24);// fetch dispatcher function from Server control

target_info = Context + 28;

handler = (**ContextDispatcher)(ContextDispatcher, &ipc_params, &callback_generic);// PolicyBase::OnMessageReady

The handler is fetched from

PolicyBase::OnMessageReady,

which winds up calling

Dispatcher::OnMessageReady.

This is a pretty simple function that crawls the registered IPC tag list for

the correct handler. We finally hit InvokeCallbackArgs, unique to Reader,

which invokes the handler with the proper argument count:

switch ( ParamCount )

{

case 0:

v7 = callback_generic(_this, CrossCallParamsEx);

goto LABEL_20;

case 1:

v7 = ((int (__thiscall *)(void *, int, _DWORD))callback_generic)(_this, CrossCallParamsEx, *args);

goto LABEL_20;

case 2:

v7 = ((int (__thiscall *)(void *, int, _DWORD, _DWORD))callback_generic)(_this, CrossCallParamsEx, *args, args[1]);

goto LABEL_20;

case 3:

v7 = ((int (__thiscall *)(void *, int, _DWORD, _DWORD, _DWORD))callback_generic)(

_this,

CrossCallParamsEx,

*args,

args[1],

args[2]);

goto LABEL_20;

[...]

In total, Reader supports tag functions with up to 17 arguments. I have no idea why that would be necessary, but it is. Additionally note the first two arguments to each tag handler: context handler (dispatcher) and CrossCallParamsEx. This last structure is actually the broker’s version of a CrossCallParams with more paranoia.

A single function is used to register IPC tags, called from a single initialization function, making it relatively easy for us to scrape them all at runtime. Pulling out all of the IPC tags can be done both statically and dynamically; the former is far easier, the latter is more accurate. I’ve implemented a static generator using IDAPython, available in this project’s repository (ida_find_tags.py), and can be used to pull all supported IPC tags out of Reader along with their parameters. This is not going to be wholly indicative of all possible calls, however. During initialization of the sandbox, many feature checks are performed to probe the availability of certain capabilities. If these fail, the tag is not registered.

Tags are given a handle to CrossCallParamsEx, which gives them access to the CrossCallReturn structure. This is defined here and, repeated from above, defined as:

struct CrossCallReturn {

uint32 tag_;

uint32 call_outcome;

union {

NTSTATUS nt_status;

DWORD win32_result;

};

HANDLE handle;

uint32 extended_count;

MultiType extended[kExtendedReturnCount];

};

This 52 byte structure is embedded in the CrossCallParams transferred by the sandboxed process. Once the tag has returned from execution, the following occurs:

if (error) {

if (handler)

SetCallError(SBOX_ERROR_FAILED_IPC, call_result);

} else {

memcpy(call_result, &ipc_info.return_info, sizeof(*call_result));

SetCallSuccess(call_result);

if (params->IsInOut()) {

// Maybe the params got changed by the broker. We need to upadte the

// memory section.

memcpy(ipc_buffer, params.get(), output_size);

}

}

and the sandboxed process can finally read out its result. Note that this mechanism does not allow for the exchange of more complex types, hence the availability of MEM_TYPE. The final step is signaling the pong_event, completing the call and freeing the channel.

Tags

Now that we understand how the IPC mechanism itself works, let’s examine the implemented tags in the sandbox. Tags are registered during initialization by a function we’ll call InitializeSandboxCallback. This is a large function that handles allocating sandbox tag objects and invoking their respective initalizers. Each initializer uses a function, RegisterTag, to construct and register individual tags. A tag is defined by a SandTag structure:

typedef struct SandTag {

DWORD IPCTag;

ArgType Arguments[17];

LPVOID Handler;

};

The Arguments array is initialized to INVALID_TYPE and ignored if the tag does not use all 17 slots. Here’s an example of a tag structure:

.rdata:00DD49A8 IpcTag3 dd 3 ; IPCTag

.rdata:00DD49A8 ; DATA XREF: 000190FA↑r

.rdata:00DD49A8 ; 00019140↑o ...

.rdata:00DD49A8 dd 1, 6 dup(2), 0Ah dup(0); Arguments

.rdata:00DD49A8 dd offset FilesystemDispatcher__NtCreateFile; Handler

Here we see tag 3 with 7 arguments; the first is WCHAR_TYPE and the remaining 6 are ULONG_TYPE. This lines up with what know to be the NtCreateFile tag handler.

Each tag is part of a group that denotes its behavior. There are 20 groups in total:

SandboxFilesystemDispatcher

SandboxNamedPipeDispatcher

SandboxProcessThreadDispatcher

SandboxSyncDispatcher

SandboxRegistryDispatcher

SandboxBrokerServerDispatcher

SandboxMutantDispatcher

SandboxSectionDispatcher

SandboxMAPIDispatcher

SandboxClipboardDispatcher

SandboxCryptDispatcher

SandboxKerberosDispatcher

SandboxExecProcessDispatcher

SandboxWininetDispatcher

SandboxSelfhealDispatcher

SandboxPrintDispatcher

SandboxPreviewDispatcher

SandboxDDEDispatcher

SandboxAtomDispatcher

SandboxTaskbarManagerDispatcher

The names were extracted either from the Reader binary itself or through correlation with Chromium. Each dispatcher implements an initialization routine that invokes RegisterDispatchFunction for each tag. The number of registered tags will differ depending on the installation, version, features, etc. of the Reader process. SandboxBrokerServerDispatcher, for example, can have a sway of approximately 25 tags.

Instead of providing a description of each dispatcher in this post, I’ve instead put together a separate page, which can be found here. This page can be used as a tag reference and has some general information about each. Over time I’ll add my notes on the calls. I’ve additionally pushed the scripts used to extract tag information from the Reader binary and generate the table to the sander repository detailed below.

libread

Over the course of this research, I developed a library and set of tools for examining and exercising the Reader sandbox. The library, libread, was developed to programmatically interface with the broker in real time,

allowing for quickly exercising components of the broker and dynamically reversing various facilities. In addition, the library was critical during my fuzzing expeditions. All of the fuzzing tools and data will be available in the next post in this series.

libread is fairly flexible and easy to use, but still pretty rudimentary and, of course, built off of my reverse engineering efforts. It won’t be feature complete nor even completely accurate. Pull requests are welcome.

The library implements all of the notable structures and provides a few helper functions for locating the ServerControl from the broker process. As we’ve seen, a ServerControl is a broker’s view of a channel and it is held by the broker alone. This means it’s not somewhere predictable in shared memory and we’ve got to scan the broker’s memory hunting it. From the sandbox side there is also a find_memory_map helper for locating the base address of the shared memory map.

In addition to this library I’m releasing sander. This is a command line tool that consumes libread to provide some useful functionality for inspecting the sandbox:

$ sander.exe -h

[-] sander: [action] <pid>

-m - Monitor mode

-d - Dump channels

-t - Trigger test call (tag 62)

-c - Capture IPC traffic and log to disk

-h - Print this menu

The most useful functionality provided here is the -m flag. This allows one to monitor the IPC calls and their arguments in real time:

$ sander.exe -m 6132

[5184] ESP: 02e1f764 Buffer 029f0134 Tag 266 1 Parameters

WCHAR_TYPE: _WVWT*&^$

[5184] ESP: 02e1f764 Buffer 029f0134 Tag 34 1 Parameters

WCHAR_TYPE: C:\Users\bja\desktop\test.pdf

[5184] ESP: 02e1f764 Buffer 029f0134 Tag 247 2 Parameters

WCHAR_TYPE: C:\Users\bja\desktop\test.pdf

ULONG_TYPE: 00000000

[5184] ESP: 02e1f764 Buffer 029f0134 Tag 16 6 Parameters

WCHAR_TYPE: Software\Adobe\Acrobat Reader\DC\SessionManagement

ULONG_TYPE: 00000040

VOIDPTR_TYPE: 00000434

ULONG_TYPE: 000f003f

ULONG_TYPE: 00000000

ULONG_TYPE: 00000000

[6020] ESP: 037dfca4 Buffer 029f0134 Tag 16 6 Parameters

WCHAR_TYPE: cWindowsCurrent

ULONG_TYPE: 00000040

VOIDPTR_TYPE: 0000043c

ULONG_TYPE: 000f003f

ULONG_TYPE: 00000000

ULONG_TYPE: 00000000

[5184] ESP: 02e1f764 Buffer 029f0134 Tag 16 6 Parameters

WCHAR_TYPE: cWin0

ULONG_TYPE: 00000040

VOIDPTR_TYPE: 00000434

ULONG_TYPE: 000f003f

ULONG_TYPE: 00000000

ULONG_TYPE: 00000000

[5184] ESP: 02e1f764 Buffer 029f0134 Tag 17 4 Parameters

WCHAR_TYPE: cTab0

ULONG_TYPE: 00000040

VOIDPTR_TYPE: 00000298

ULONG_TYPE: 000f003f

[2572] ESP: 0335fd5c Buffer 029f0134 Tag 17 4 Parameters

WCHAR_TYPE: cPathInfo

ULONG_TYPE: 00000040

VOIDPTR_TYPE: 000003cc

ULONG_TYPE: 000f003f

We’re also able to dump all IPC calls in the brokers’ channels (-d), which can help debug threading issues when fuzzing, and trigger a test IPC call (-t). This latter function demonstrates how to send your own IPC calls via libread as well as allows you to test out additional tooling.

The last available feature is the -c flag, which captures all IPC traffic and logs the channel buffer to a file on disk. I used this primarily to seed part of my corpus during fuzzing efforts, as well as aid during some reversing efforts. It’s extremely useful for replaying requests and gathering a baseline corpus of real traffic. We’ll discuss this further in forthcoming posts.

That about concludes this initial post. Next up I’ll discuss the various fuzzing strategies used on this unique interface, the frustrating amount of failure, and the bugs shooken out.